Published on

May 6, 2025

.png)

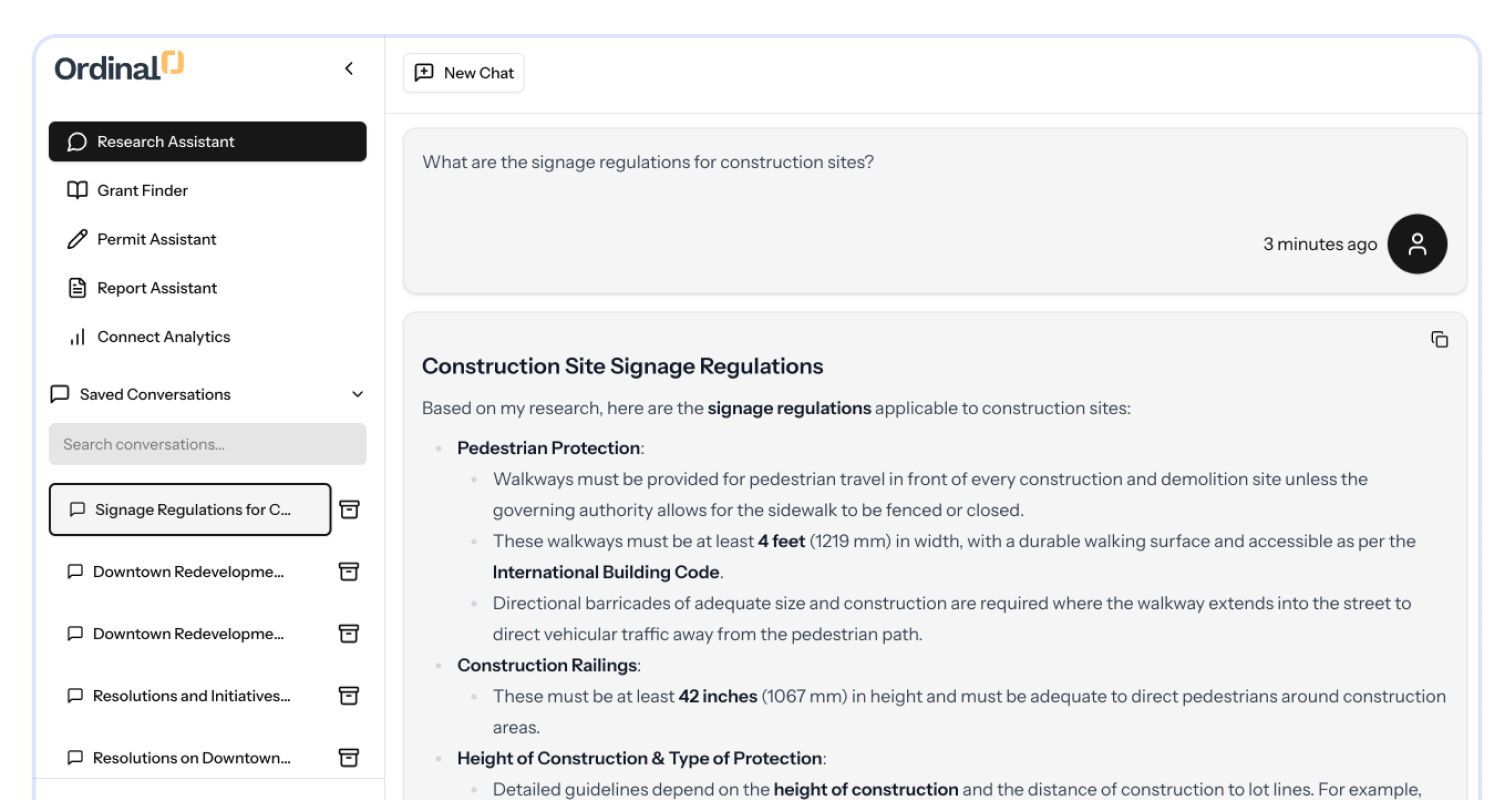

AI and data are rapidly reshaping the landscape of modern city planning. Today, large language models (LLMs) are used to analyze built environments, computer vision systems monitor traffic flow and sidewalk conditions, digital twins are used to simulate city changes, and AI assistants are performing research tasks. These technologies offer a remarkable shift: not only can we plan more efficiently, we can plan more intentionally.

But with this opportunity comes a critical responsibility. Technology may appear objective, but it is not neutral. AI systems are shaped by the data they are trained on, and if that data reflects historical inequities, those inequities can be embedded and scaled. Without deliberate design and oversight, AI has the potential to reinforce the very disparities that city planners aim to correct. The question is no longer whether we will use AI in planning, but how we will ensure it is used in service of equity.

Historically, urban planning has been an exclusionary practice, enforced by policy that prioritized the interest of white, affluent populations, while systematically displacing and disinvesting in marginalized communities. This biased approach has resulted in deeply entrenched social inequities, where access to resources, social services, and economic opportunities are often dictated by race, class, and geography. In turn, these prejudices have been woven into the fabric of our policies, institutions, and technologies.

As the world becomes increasingly digital, these historical biases risk being encoded into evolving technologies. Without intentional design that embeds equity through participatory design processes, the centering of voices and lived experiences of marginalized communities, and the deliberate utilization of underrepresented voices in a justice-oriented approach, emerging technologies risk reinforcing harmful rhetoric that enforces systemic inequalities.

Data is a powerful tool that assists in making informed decisions, providing insights into trends, behaviors and outcomes. It allows policymakers, businesses, and researchers to analyze patterns to create evidence-based decisions, and provide implications for future research. When used correctly, and responsibly, data can highlight areas for improvement, optimize resources, and drive innovation. However, its effectiveness from an equity standpoint relies heavily on accurate inclusive data that truly reflects the experiences and needs of all communities. Quantitative data is often viewed as objective, however, it does not accurately capture lived experiences, systemic biases, and gaps in representation. This lack of comprehensive and inclusive data catalyzes a cycle of disproportionate harm. Leading to far-reaching consequences within the built environment.

Although redlining was officially outlawed over fifty years ago, its legacy remains deeply embedded in the fabric of urban development. Today, discriminatory practices continue under different names—through racial steering, exclusionary zoning, and other subtle forms of housing discrimination. For example, single-family zoning policies, while seemingly neutral, are inherently exclusionary. They concentrate development, economic opportunity, and essential services in affluent, often racially homogenous neighborhoods, while low-income and "missing middle" communities are systematically underfunded and overlooked. In housing, the impact of gentrification and displacement—often driven by skewed economic data—continues to displace long-standing residents. Economic models that overlook historical disinvestment and the absence of generational wealth in Black communities tend to undervalue these neighborhoods. As a result, they are deemed less viable for investment, perpetuating cycles of neglect and exclusion by developers and policymakers alike.

These patterns of exclusion are not limited to housing. A persistent lack of representation in decision-making has allowed policies to evolve in ways that reinforce systemic biases across multiple sectors—including the criminal justice system. Biases embedded in predictive policing tools have led to the disproportionate surveillance and criminalization of minority communities, exacerbating existing inequalities and eroding trust in public institutions.

Public health data similarly reflects a troubling pattern of exclusion. Chronic underreporting of issues disproportionately affecting Black women and other marginalized groups reveals the limitations of traditional data sources. These gaps not only obscure the true scope of health disparities but also lead to policies that fail to address the specific needs of these communities.

The same inequities appear in mobility and transit planning. Car-centric infrastructure is prioritized, while marginalized communities are left with inadequate public transportation, limited walkability, and poor connectivity to jobs and services. This further isolates residents and reinforces economic and social barriers.

In education, schools in disinvested neighborhoods—often in communities of color—receive poor ratings and are chronically under-resourced. These schools struggle to meet the needs of their students, contributing to educational disparities that echo into adulthood and across generations.

Collectively, these challenges are rooted in flawed data systems—data that often ignore systemic barriers, historical context, and community voices. When data fails to reflect lived realities, it reinforces cycles of disadvantage rather than disrupting them.

To move toward more inclusive and equitable urban development, we must critically examine and reframe the data we rely on. This means developing systems that account for past injustices and recognize future possibilities—tools that empower rather than exclude, and policies that invest in the communities long overlooked.

To truly serve the public good, cities must go beyond simply adopting AI. They must design it with equity at the core, and that starts with the data. Equitable AI in city planning means using localized, community-validated data that reflects the diversity of experiences, needs, and priorities across neighborhoods. Relying solely on historical datasets without context can reinforce patterns of disinvestment and exclusion. Instead, cities should seek out participatory methods for building datasets, ensuring the inputs used to train AI tools reflect current realities and lived experiences.

Transparency is also critical. Planners, staff, and residents should be able to understand how an AI tool arrives at its conclusions. This means prioritizing models with explainable outputs and clear citations. In planning, where decisions can have long-term impacts on equity and livability, black-box algorithms have no place. Human-in-the-loop systems further support ethical use by keeping people in control, allowing for contextual judgment and local knowledge to shape final decisions.

It is crucial to create policies and guardrails that prioritize social responsibility to ensure that AI technologies are developed and deployed ethically and transparently. By doing so, we can protect the most vulnerable communities, prevent harm, and maximize the positive impacts of AI during planning practices. Some strategies include:

As AI becomes a more common tool in city planning, it’s essential to remember that data can inform decisions, but it can’t replace dialogue. Community engagement has always been a cornerstone of equitable planning, and that doesn’t change with the introduction of AI. In fact, it becomes even more important.

Effective community engagement in building AI models requires intentional, sustained involvement from project inception. Rather than relying solely on quantitative metrics, developers should prioritize rich, qualitative feedback that reflects the lived, nuanced experiences of communities that have been historically inconvenienced by data. It is essential to recognize that diversity alone does not equate to equity or equality; meaningful representation demands that everyone not only has a seat at the table but also a voice that is actively heard and valued. Some methods that may contribute to equitable approaches to community co-creation models include:

In this way, AI becomes a complement to public engagement, not a substitute. It can expand the reach and efficiency of planning work, but it should always be followed by thoughtful conversations with the people those decisions will affect. Combining digital insight with lived experience is how we build cities that are both smart and just.

AI and data are undeniably shaping the future of planning. They’re helping cities respond faster, see patterns more clearly, and make decisions with greater confidence. But these tools don’t come with built-in values. It’s up to us—as planners, technologists, and public servants—to shape the intent behind the systems we adopt and ensure they reflect the communities we serve.

As we integrate AI into the everyday work of planning, we have a responsibility to embed equity into every layer of our digital infrastructure. That means asking hard questions about data, involving residents early and often, and holding our tools to the same standards of fairness and accountability we hold ourselves to. The future of city planning can be smarter, but only if it’s also more just. Let’s build that future together.

Ready to see Ordinal in action? Book some time with our team and we’ll show you just how valuable this could be for you and your staff.